A Volcano in Transition

The press covered the May 2018 eruption of the Kīlauea volcano in great detail, reporting the shift in lava flows from a barren area near Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HVNP) to the residential community of Leilani Gardens, the destruction of roughly 700 homes, and the subsequent collapse of Halemaʻumaʻu, Kīlauea’s central crater. The press also highlighted the new lava deltas that extended the land area of the Big Island, and recently reported on an intriguing new development since Kīlauea stopped erupting—the presence of water in the crater. Little, however, has been written about the possibility that ancient, but similar events, were captured in Hawaiian oral history or that those legends may hint at explosive future events.

The press covered the May 2018 eruption of the Kīlauea volcano in great detail, reporting the shift in lava flows from a barren area near Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HVNP) to the residential community of Leilani Gardens, the destruction of roughly 700 homes, and the subsequent collapse of Halemaʻumaʻu, Kīlauea’s central crater. The press also highlighted the new lava deltas that extended the land area of the Big Island, and recently reported on an intriguing new development since Kīlauea stopped erupting—the presence of water in the crater. Little, however, has been written about the possibility that ancient, but similar events, were captured in Hawaiian oral history or that those legends may hint at explosive future events.

But first some background. Geologists believe that all the Hawaiian islands, as well as a long line of seamounts extending far to the northwest, arose through volcanic activity at a single hot spot in the middle of the Pacific tectonic plate. That hot spot produced layers and layers of lava that grew over millennia emerging from the ocean to form the mountain tops we know as the Hawaiian Islands, as well as a long series of lesser mountains still submerged below sea level. Over the same millennia, the Pacific tectonic plate moved slowly to the northwest, carrying each of the newly formed mountains with it to their current location.

These island-forming volcanoes are all extinct, except for those on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi and Lōʻihi, a seamount off the southeast coast of the Big Island. On the Big Island, the Kohala Mountains and Mauna Kea are believed to be extinct, while the mountain volcanoes of Mauna Loa, Hualālai and Kīlauea all remain active. Of these active volcanoes, Hualālai most recently erupted around 1800, while Mauna Loa did so in 1984. All the eruptive activity since then has been at Kīlauea.

Historical records and observations of lava flows indicate that Kīlauea cycles through alternating phases of explosive eruptions and effusive flows when lava more or less spills from the ground. For the last couple of hundred years, the volcano has been in an effusive phase. One such flow lasting from 1983 to May 2018 erupted from just outside HVNP and formed the Puʻu ʻŌʻō cone on Kīlauea’s northeastern flank. In May 2018, the Puʻu ʻŌʻō cone collapsed and the eruption shifted north to the residential community of Leilani Gardens. From May to August 2018, more than 60,000 earthquakes shook Kīlauea, and Halemaʻumaʻu, it’s central crater, collapsed. Since then, Kīlauea has been quiet—a dormant period that continues as of this writing.

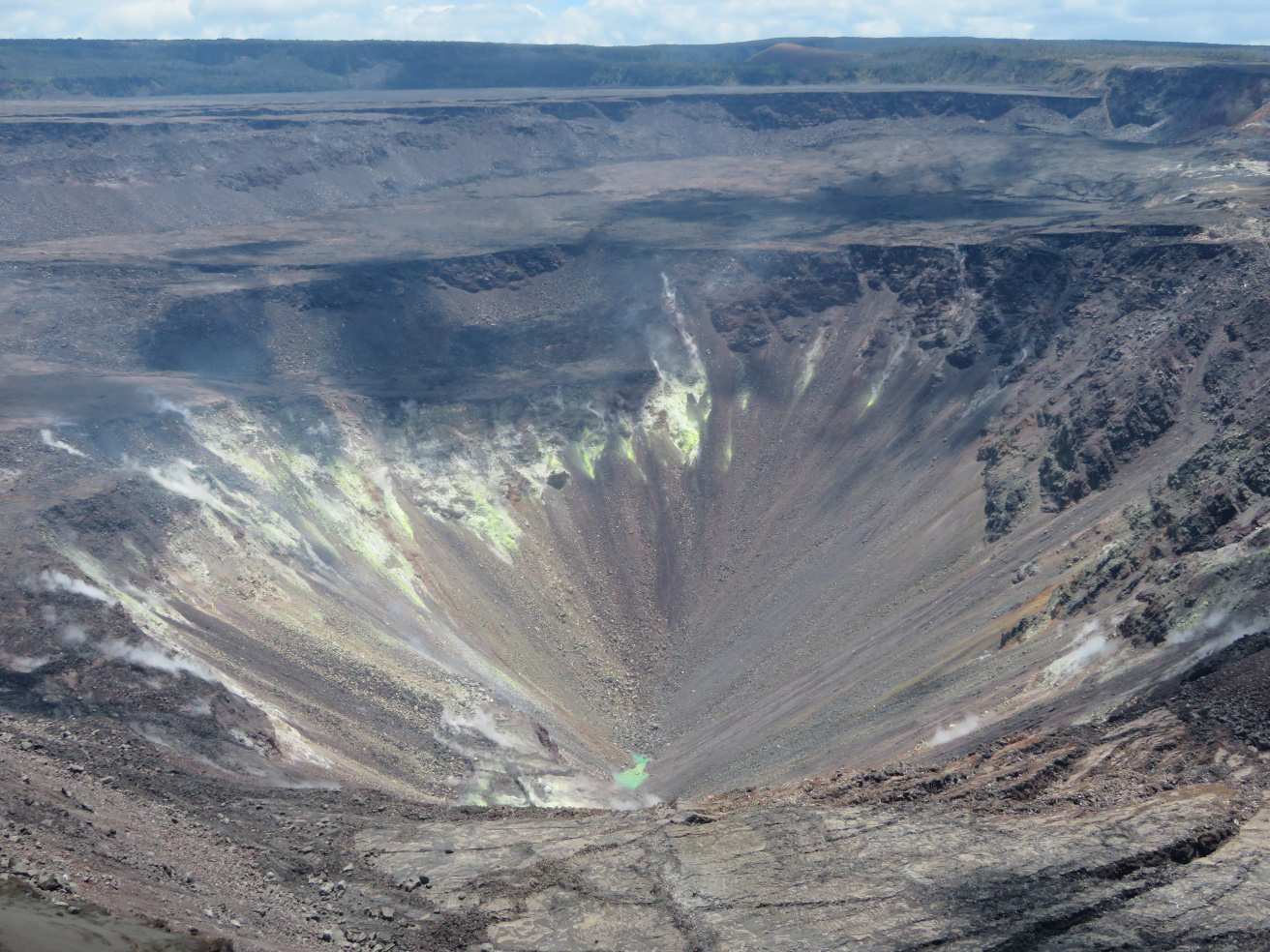

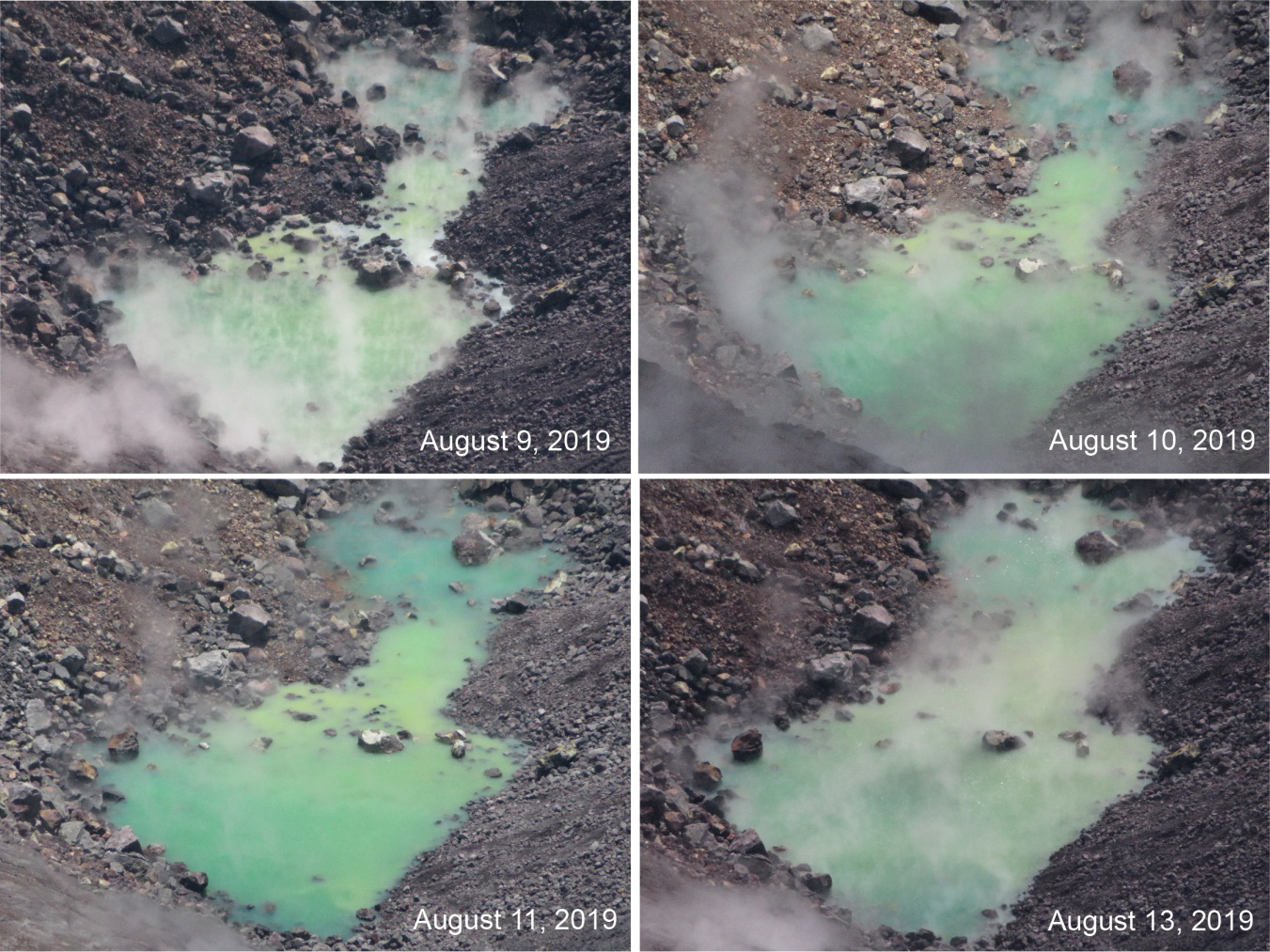

Now, however, something historic is happening at Kīlauea. For the first time in recorded history, there is a pool of steaming hot water about 158 degrees at the bottom of the crater, and it’s growing bigger and deeper, forming a small lake. Scientists haven’t verified its source, but since the floor of the collapsed crater is now below the water table, the pool is most likely groundwater.

More importantly, USGS scientists are unsure of the significance of this lake. They speculate that it could be a harbinger of Kīlauea’s transition from its long-standing effusive stage to a future explosive period. History tells us that magma from the hot spot in the Pacific tectonic plate, pushed up by forces deep within the earth, will with time refill the crater. As the magma rises, the searing hot gases trapped within will expand and escape, and superheated rock and gases could cause water in the crater to flash into steam causing or intensifying explosive eruptions.

Water in the Kīlauea crater, August 2019. Courtesy USGS.

As I mentioned above, the lake at the bottom of the crater is unique in recorded history. Interestingly, there are Hawaiian legends told in chants and stories, collected by Reverend Ellis, a 19th-century Western missionary and one of the first people to chronicle Hawaiian lore, that refer to water inside Kīlauea and support the scientific speculation that the volcano is undergoing a transition to an explosive phase. According to these old Hawaiian chants, Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanic fury, arriving from the island of Kauai to take up residence in Kīlauea, left her lover Lohiaʻu on Kauai. Pele made a bargain with her sister, Hiʻiaka: If Hiʻiaka would retrieve Lohiaʻu from Kauai within a span of 40 days, Pele would refrain from burning Hiʻiaka’s favorite ʻōhiʻa tree forest.

The growth of the ponds in the Kīlauea crater. Courtesy USGS.

After many adventures, Hiʻiaka succeeded but not within the allotted 40 days. Thus, when Hiʻiaka finally did return to Kīlauea with Lohiaʻu, she found that Pele had ravished her precious forest with lava flows. This part of the legend may well refer to the ʻAilāʻau lava flow, known to scientists as a massive 60-year lava flow between roughly 1410 and 1470 that covered most of Kīlauea and undoubtedly destroyed many acres of surrounding forest.

But oral history gets even more interesting. Hiʻiaka retaliated against Pele by making love to Lohiaʻu. Infuriated, Pele is said to have buried Lohiaʻu deep under Kīlauea. Desperate to find her buried lover, Hiʻiaka dug up the crater flinging great quantities dirt and rocks miles into the air. Geologists know from radiocarbon dating that the Kīlauea crater collapsed sometime between 1470 and 1500, so, again, this legend may well be an accounting of the late 15th-century crater collapse.

Most relevant to today, however, is the chant’s allusion to Pele’s warning to Hiʻiaka against digging too deep lest she hit water—advice that went unheeded.

Another moʻolelo, a story or legend, tells of a turbulent love affair between Pele and Kamapuaʻa, a Hawaiian rainwater deity. This tempestuous relationship became acrimonious as they engaged in many battles during which Kamapuaʻa tried to drown Pele, while she fought back by hurling fire and rocks at Kamapuaʻa, ultimately driving him into the sea. This legend may well have arisen from a long period of explosive eruption at Kīlauea from about 1500 to 1790, with particularly violent activity in about 1600 and 1790.

Interestingly, the 1790 explosive eruption also marked a turning point in Hawaiian history. At that time Kamehameha I and Keōua, then the most powerful chiefs on the Big Island, were fighting for supremacy. The 1790 eruption reportedly killed many of Keōua’s warriors and camp followers, handing control of the Big Island to the future king of all Hawaii.

Only in time, as oral history might foretell, will we know if the 2018 collapse of the Kīlauea crater and the appearance of a growing pond of water will mark another turn in the history of the Big Island.

Finally, I would be remiss if I did not credit Don Swanson and USGS for the extensive research into the scientific and historical materials from which this article is drawn.